By ALIBHAI-BROWN YASMIN (1969-72 ARTS: LITERATURE)

Next stop Makerere, to the women’s hall of residence, Mary Stuart Hall, a ghastly sixties tower block, for me very heaven. It was the end of 1969 just as the country was getting calamitously close to fragmentation. The campus swept up a hill lush with grass, green as the colour of life itself. Nandi flame trees, and others high and wide and ancient, provided shade for students reading books and debating ideas. The main building stood at the top, white and imposing with a bell tower. Shoots of new possibilities were all round us. We would retell the story of our country. Africa was neither intellectually barren nor uncivilized before the white man came. We were determined- black, brown, and white Makerereans - to make Uganda proud and great one day.

I joined the Literature department. The European cannon was still faithfully taught but had to compete with compelling new voices. Paul Theroux excited us with his indefinable but extraordinary talent; we were reading James Baldwin and emerging black American writers, African dramatists, and novelists such as Wole Soyinka and Chinua Achebe and V.S. Naipaul who never returned the love we had for his books.

The author, Alibhai-Brown Yasmin

Some African tutors were systematically unfair to the Asians and possessive of the emerging nation - making up for history, I guess. But mostly it felt like we were travelling together to another country where race was irrelevant, and rainbows appeared every day.

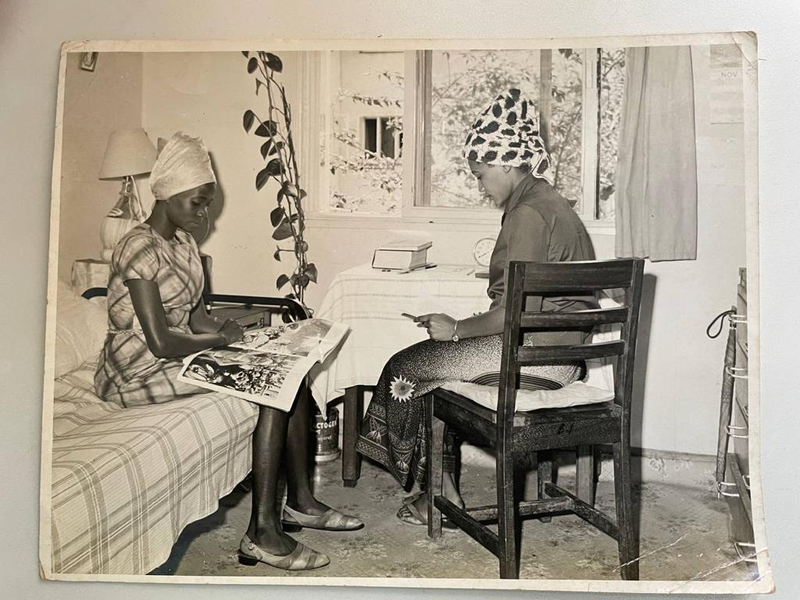

I was intellectually stimulated like never before, surrounded by friends, music, books, drama. I shared a room with two African girls, Jane and Sophie, young women who, like me, never imagined they would, one day, be at university. Such cross racial room sharing was still rare.

Sophie was tall and big with a laugh to shake Kilimanjaro. Her life held the serial tragedies of Uganda - relatives killed by Obote and later Amin, exile, HIV, and the funeral procession that never seemed to end. Jane was beautiful and distant, so irresistible to men. Messages were left for her on the message board, sometimes the whole board. “Come and jig with me O lady Jane”. Unfortunately, she fell for Anton, the black Californian with a tight body and mean eyes, a poseur and cheat who wore a Che beret.

These black Americans were root seeking they said. Actually, they were a pain. Anton called Jane his “jungle bunny” and she, smitten, smiled with much pleasure. He took her money. Sophie warned her: “Jane, are you foolish or what? Sister get some sense.” But love, as I too later discovered, makes you lose all sense.

Food was terrible at Uni - over-fried eggs, posho and red beans, stringy meat and matoke, tasteless mince and soggy rice. Precious home-made pickles made it edible. Jena sent over jar after jar of marmalady mango concoction, a favourite among Asians and African students too who had not previously been exposed to Asian cooking. They loved it so much they stole many of my jars.

You could call that emerging integration, a small sign of unity. However, away from campus the mood was bleak. Africans were adjusting to Obote’s brutal leadership while Asians hid in their dens of comparative plenty and retreated into remembered previous lives.

Some Asian undergraduates developed two personas, one obedient and yielding to family traditions and old structures, exaggeratedly so, to conceal the other who was free and liberal and in revolt against the apartheid that had served their people well once. In my second year I made a lifelong Asian friend, another oddball like me, but more of a loner. Farial was a medical student from Dar-es-salaam and a non-conformist Ismaili. She was quiet and sulky and determinedly dowdy. I was loud and sparkly and fashion mad. Unfathomable why we were drawn to each other. We remain firm buddies - even though she is a patriotic American doctor in Pittsburgh permanently perplexed by what I do and why.

In the mosque, as times got harder, the low tables of food offerings were over laden. Only now, the simple food had gone. The mood had swung the other way. It was time for extravagant dishes, desperate measures, hopeless hope. Sugar had gone up shockingly in price, so more atoning sweetmeats were brought in and the seero, (small bites of semolina) was given to congregations at the end of service with holy water.

One morning I heard no birdsong. It was the 25th of January. I opened the yellow cotton curtain of my small room in college on Floor 6 and a baby bat fell on the floor. It was softer than I expected when I touched it, and dead. After about half an hour, students started going down for breakfast and normal life seemed to resume as I got dressed. Then Sophie, my roommate the previous year, rushed into my room. Her black skin had lost its brilliant sheen and appeared more ash grey than black:

Mary Stuart girls in their room in the the 1970s

“Yasmin, stay in, stay in, don’t go anywhere, I’m telling you. The military has taken over - Obote is out, we don’t know any more, don’t go anywhere I am telling you.”

Round and round she went with the same words, again and again, sometimes actually turning herself, not stopping so I could ask her questions, just filling me with the encircling dread she felt.

Now our tall tower residence block itself seemed to ululate, spasms and waves were felt as if the building was swaying. Loretta, a Muganda, a brilliant and beautiful English undergrad rushed into my room with a knife in her hand. She said she wanted to kill herself before soldiers killed her. It was a scene from a melodramatic movie - she was hysterical, her hair literally standing up, wearing only bra and knickers pushing the knife into her heart as I yelled for help. The dead bat stopped her. She saw it where it was still lying and screamed like she was being murdered. This cry brought the others in, and they took the knife off her. We threw the bat into the valley below from the balcony and it fluttered down, through the silence outside, thick as a fog.

The radio played My Boy Lollipop all day interspersed with horrible warnings from military men of curfews and announcements about the new order which would not tolerate any troublesome opponents. (Throughout Africa, opponents are always thought too much trouble.) “Uganda is being cleaned up.”

The next day there was rejoicing in the streets. The Baganda were delirious. Obote, who had destroyed their king and kingdom was out, the man of the people, Idi Amin, was in. Students celebrated by taking time off lessons and making daytime love in their rooms. Another bright beginning, another dark ending. Asian businessmen were well pleased. That communist Obote would no more get his hands on their assets. Some of them knew Amin and had bribed him often. But they were nervous too during this uncertain time.

Asian parents drove over and took away their girls. Only three Asian women were left behind, two who came from outside Uganda and me. We stayed, drank lots of sweet tea made of evaporated milk to steady the nerves. It was a test of sorts, and we didn’t cope with dignity. Often lying tight in one bed the three of us whimpered like lost children in dark fairy tales. Mamti, the Sunni Muslim prayed eight times a day instead of five, double prayers. Her prayer mat was always with her and if any of us touched it, she went quite berserk. It had become her comfort blanket; my yellow quilt was mine.

Makerere seemed to be full of quiet men watching us. We whispered even when with trusted friends in private spaces and soon mistrust spread. Metaphors were used, codes made up and changed frequently. You quickly learn how not to say the wrong thing, it becomes second nature.

Amin’s soldiers were seen in the college bar, the canteen (run by Kanubhai, a man with one ear, always lugubrious and after the coup, suicidal) and the main hall where we once we bopped with the energy of a new nation. If they found groups of friends walking and talking it was considered a plot.

One day in May 1971, we gathered on campus to protest against the regime. Tanks suddenly appeared at the main gate. Tear gas was released, shots were heard, eight students were snatched and taken, never to return. I was there, in a checked mini dress, a scarf around my head (it was a bad hair day), knee length socks and the bravery of a drunken fool who walks up in front of fast cars. I have a photo of that too, of us fleeing with smoke and panic all around us.

After that day, the process of extermination of intellectuals gathered pace. Like Pol Pot, Amin knew the country would be easier to subjugate if he could rid it of academics, lawyers, constitutionalists, writers, artists, journalists, and educators. He also suffered from a pathological inferiority complex. It was payback time for those of high education who made Amin feel low.

The President turned up at Makerere that June for graduation day. He was dressed in full academic gear and insisted he was going to conduct the entire ceremony, and personally shake hands with all those who had passed their finals. Students who tried to walk out of the hall were roughly pushed back in by soldiers. I was wearing the shortest, silky yellow dress, sunny and bright even though we were living through the most terrible period of history. Put it down to irrepressible, obtuse optimism.

Mary Stuart Hall in 2020

Then the night raids started, suddenly at about three o’clock we would hear heavy jackboots striding up the stairs, floor after floor. You started and shook when the hard steps approached, then a sobbing relief would overcome as the footsteps got more distant, then faded into a faraway echo. Rather than go out into the corridor to the toilets, we used the box-shaped, opaque, glass ceiling lamp shades instead.

One night they took away Esther and her twin Mary, students of agriculture, fun, always popular with the boys. Esther came back a week later, shuffling painfully and unwilling to talk. Both sisters had been taken to the nearby barracks to be gang-raped until the soldiers grew bored of them and needed new meat. They both went back home without graduating. They would have been the first young women in their extended family to get to this level of education, but it was not to be. All that money saved and donated by their village and relatives came to nothing.

There was worse to come. Doors were kicked down, every night and the screams ricocheted. Soon it became clear that they were carefully selecting the Baganda and Langi females from Obote’s tribe, and most of all Acholi women. Names were all on the doors, so tribes were easily identified.

Some of the women the soldiers came looking for hid in the rooms of the Asian students because strangely enough, the soldiers never touched us during this orgy. It is as if we still had around us an aura, a circle into which they didn’t dare step, men with guns and nothing to lose.

A handsome student who was a part-time newsreader on TV was escorted every night to the studios by soldiers, for by that time we were living under an interminable series of curfews. Rocky was his nickname, and he played the trumpet like no other. One night, a few weeks on, Rocky’s protectors said they felt they wanted to shoot a part of him. He was free to decide which bit. Before fear turned his words to gibberish, he chose his left foot. They shot it and laughing all the way, drove him to hospital.

He too left Makerere and vanished into the vast countryside. Victor Hugo wrote in Les Miserables: “Liberation is not deliverance.” Ugandans by this time knew exactly what that meant.

Independence had given them two dictators and fast rivers of blood.

Makerere University, where so many of us had the best days of our lives, lost its joy, purpose and intellectual energy. We need to keep those alive through our memories.

This story was first published in the Makerere University Alumni Group 2020 History Book

Related News

![]() Please join hands with the Makerere University Endowment Fund as it works towards attracting & retaining the best faculty, providing scholarships, and investing in cutting-edge research and technology.

Please join hands with the Makerere University Endowment Fund as it works towards attracting & retaining the best faculty, providing scholarships, and investing in cutting-edge research and technology.