By Arinaitwe Rugyendo

By 1994, Makerere University was an exclusive enclave of higher education, accessible to a few highly educated citizens amidst a vast population who could afford the fees but were not admitted. This changed with Prof. Wasswa Balunywa, then Dean of the Faculty of Commerce, and until recently the Principal of Makerere University Business School (MUBS), who began admitting fee-paying students to evening programmes. A study by Professors Nakanyike B. Musisi and Nansozi K. Muwanga, titled “Makerere University in Transition 1993–2000: Opportunities & Challenges,” highlights that the push for institutional reform began in 1992, when greater autonomy and a market-oriented approach were adopted. In his 1992 commencement address, President and Chancellor Yoweri Museveni announced his plan to step down as chancellor and endorsed the university’s demand for autonomy, provided it took on some fundraising responsibilities. The first systematic planning spanned 1992 to 1995, with a five-year development plan, though deemed too ambitious and unfocused to be adopted. By 1994, the University Council decided that faculties could fill vacancies with private students if government-sponsored slots remained unfilled. In 1995, all faculties were allowed to operate revenue-generating evening courses. By 1999, tuition-paying students outnumbered government-sponsored ones, with 10,000 new undergraduates, and only 20% government-sponsored. Prof. Balunywa spoke to The Legacy’s about the 30-year transformation brought by private sponsorship at Makerere University. Below are the excerpts:-

Prof. Wasswa Balunywa speaking at the Makerere@100 Stakeholder Mobilisation Event

Q: How did this whole idea start?

A: It was not easy to get the government to accept these ideas of having private students in the university. People questioned if we wanted degrees to be bought. However, for growth, change is necessary. The introduction of private students aimed to bring in more students and utilize the university more effectively, thus increasing access to education. At the time, Makerere enjoyed autonomy, with the Senate holding decision-making power. The Council could only request the Senate to reconsider, but not outright reject academic issues. Despite initial skepticism, the decision to admit private students was ultimately a tremendous success. We anticipated a break-even point of 87 students but received over 200 applications, with about 125 students enrolling. This led to significant changes not only in the Faculty of Commerce but across Makerere and other institutions. The World Bank recognized the liberalization of higher education, and Makerere's initiative played a key role in this transformation.

Q: What were the initial challenges you faced in implementing the private sponsorship scheme?

A: The initial challenges were mainly internal. As we started making money, success bred envy. Most of us did not have PhDs, and people saw us as inexperienced. Many expected us to fail, but we exceeded expectations. The money allowed us to buy necessary materials and hire experienced staff. The initial envy from colleagues was the primary challenge, but soon they too wanted to replicate our success. Once the programme took off, it ran smoothly. We started offering short-term training programmes that generated additional revenue, further enhancing our operations.

Q: How has the scheme impacted the diversity and inclusivity of the student body at Makerere University?

A: The impact of the private sponsorship programme at Makerere University needs further study. However, a noticeable shift in student demographics occurred. In the 1980s, students predominantly came from good schools in specific districts, mainly around Kampala. The programme aimed to promote inclusivity, but the concentration of students remained in certain areas, not reflecting a nationwide spread. Payment issues possibly hindered broader inclusivity. Gender inclusivity improved with the introduction of the 1.5 point programme for female students in the early 1990s. This helped more women enter various professions. While diversity in terms of origin and background increased slightly, Makerere failed to fully capitalise on its esteemed position in East Africa to attract a wider student base.

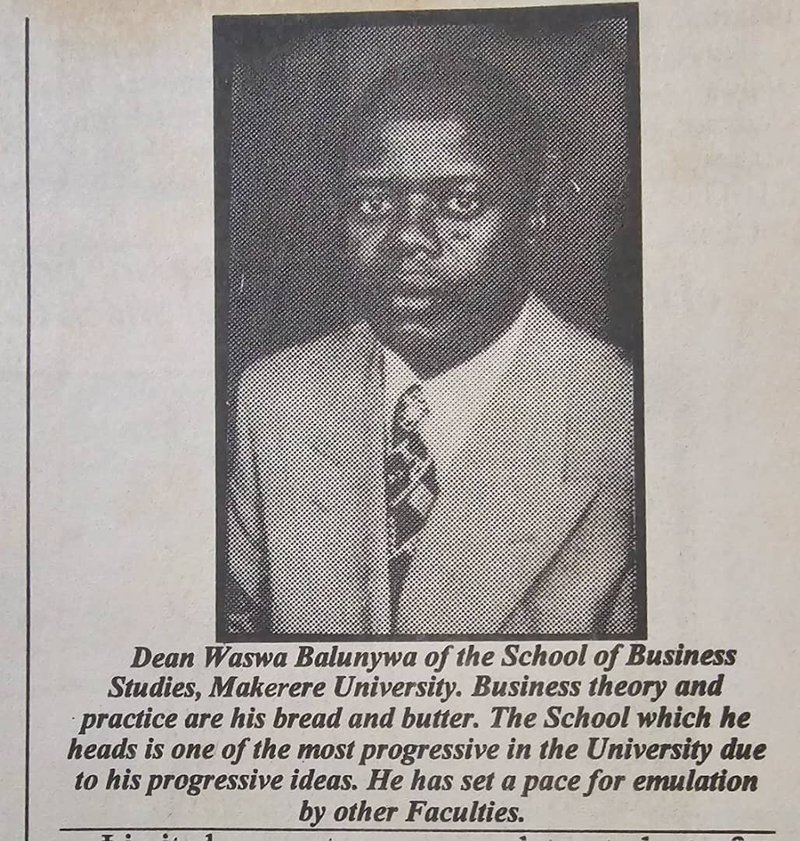

Prof. Balunywa appearing in the November 1997 issue of The Uganda Educational Journal

Q: How then did the surge in student numbers affect the university's status and its neighborhoods?

A: The increasing student numbers had a significant economic impact on the university’s financial status and neighbouring areas. For example, in the Nakawa-Bugolobi-Kiswa area, hostels, restaurants, salons, and shops sprang up, creating a bustling economy. Similar developments occurred around other institutions like Uganda Martyrs University in Nkozi and Uganda Christian University in Mukono. These businesses catered to the needs of the growing student population, providing food, accommodation, transport, and entertainment services. The local communities benefited economically, and new businesses, such as Shaka Zulu Restaurant emerged to serve both students and the general public. This economic boom persisted even during holidays when a small number of students remained in the area. The private sponsorship scheme has undoubtedly transformed Makerere University and its surroundings. By embracing change and innovation, Makerere set a precedent for other institutions to follow.

Q: In what ways has this scheme transformed the higher education system in Uganda as a whole?

A: The initiation of private programmes at Makerere University, which later spread to other institutions in Uganda and across Africa, has had a significant impact on higher education. The idea of allowing fee-paying students faced initial skepticism, with concerns about the quality and eligibility of these students. However, over time, it was proven that private students could achieve high academic standards, with many earning first-class honors. This initiative increased access to education, making it possible for more people to pursue higher education if they could afford it. It also shifted the responsibility of funding education to parents, encouraging them to work hard and plan their families accordingly. Like I have just mentioned, the scheme spurred economic growth in areas surrounding universities. This economic activity created jobs and improved local infrastructure..

Q: What about Makerere University Business School?

A: At Makerere University Business School (MUBS), the scheme led to an increase in staff and the establishment of a robust staff development programme resulting in numerous PhD holders and professors. The private sponsorship programme also enabled institutions to generate their own revenue, reducing reliance on donor funding. This autonomy allowed for the development of infrastructure and services that benefited both students and the local community. This programme has had a lasting impact on the higher education system in Uganda by increasing access to education through revenue generation and staff development.

Q: How do you see the future of higher education funding in Uganda evolving in the next decade?

A: The future is bright save for funding of higher education which currently lacks fairness. A policy is needed to create a level playing field. The government should fund all science education at every level, including university and tertiary education, to ensure transformation through science and technology. Emphasis should be on equipping laboratories and encouraging innovation. Infrastructure in public universities should have some degree of equity based on student numbers and programme types. Quality facilities such as libraries and teaching spaces are essential. Funding should also consider government plans and workforce needs, whether in oil and gas, procurement, history, or geography. Salary levels, although appreciated, may deter private institutions due to high costs. Loans should be given to students in private universities rather than those already in government-funded institutions to manage resources better. Attention to underdeveloped areas like Karamoja is vital to encourage more participation in higher education.

Q: Would private sponsorship alone suffice?

A: Private programmes can cover variable costs but not major infrastructure like buildings and equipment. Revolutionary thinking is needed to disrupt the sector positively. Online learning can lower costs but must be carefully implemented due to its mixed advantages and disadvantages. Adjusting teacher-student ratios to have more students per instructor can also reduce costs. Future funding needs to focus on reducing tuition fees to increase access. The trend of sectarian universities should be reconsidered in favour of supporting existing institutions like Makerere to expand and provide quality education across regions. Government should withdraw from managing hostels, allowing these to be rented out to students, including those in private programmes. Increasing access, lowering costs, and ensuring quality infrastructure are key to improving higher education in Uganda. We need disruptive innovators to drive these changes.

Q: How has the private sponsorship scheme influenced the financial stability and growth of Makerere University?

A: Funding a university is not easy, and when we started the program in 1991-1992, we had a breakeven point of 87 students but managed to enroll about 125, which was nearly 50% more than expected. This additional income allowed us to buy scholastic materials, computers, and vehicles, although it couldn't entirely replace government funds. Initially, the scheme provided financial relief by covering labour costs and running expenses. Makerere had an advantage with its existing infrastructure, which private universities often struggle to build without government or donor support. For instance, we planned to construct a ten-storied building at Makerere before moving to Nakawa, but the move revealed additional costs like maintaining a large compound, buying computers and vehicles, and handling other logistics.

Government support, such as from the African Development Bank, helped us build substantial infrastructure like a library at MUBS. Relying solely on student fees wouldn't have sufficed for such projects. The scheme's initial impact on financial stability has diminished, especially with the introduction of higher salaries for lecturers and professors. Private institutions find it challenging to match these salaries, causing financial strain.

Q: When you look back 30 years ago, what sort of success story do you see out of this?

A: The impact of private sponsorship has been tremendous. The number of privately sponsored students now exceeds those on government sponsorship. The government sponsors fewer students across its 10 universities, with Makerere having a large share. Makerere has around 40,000 students, with about 4,000 government-sponsored students being admitted each year. At MUBS, the number of government-sponsored students was around 1,200 out of nearly 20,000 total students when I left. The programme’s success is evident in the gratitude from beneficiaries. Many people thank us for giving them the opportunity to study, especially those who might not have had the chance otherwise. The MBA programme, never government-sponsored, has produced a knowledgeable group of managers contributing significantly to the country's development. Overall, private students have played a significant role in running the country due to the limited number of government-sponsored students.

Prof. Balunywa speaks at a #MakerereAt100 commemoration event

Q: You mentioned impact in other private universities. Do you think the success of this scheme could have inspired their founding?

A: Yes, the success of the scheme indeed inspired the establishment of private universities. Today, there are 11 government universities and about 40 private universities. The most successful private universities are religiously affiliated, such as the Islamic University in Mbale, Uganda Christian University in Mukono, and Uganda Martyrs University in Nkozi. These institutions have received substantial external funding to build infrastructure. Pure private universities were motivated by the feasibility of running institutions through student fees. However, they face challenges, particularly in paying salaries. Many struggle with financial stability due to insufficient student numbers and attempting to run too many programmes with small enrollments. Private universities must address the issue of associating costs with income. Government universities benefit from higher salaries and loan schemes, which are not aligned with the income levels of private institutions. The loan scheme should focus on private universities to help them compete. Government funding and infrastructure support for private institutions are crucial to their sustainability. Private universities played a significant role in expanding access to higher education but now face financial challenges exacerbated by rising costs and the need for better financial planning. Resolving these issues requires strategic support and innovative solutions to ensure their continued contribution to the education sector.

Related News

![]() Please join hands with the Makerere University Endowment Fund as it works towards attracting & retaining the best faculty, providing scholarships, and investing in cutting-edge research and technology.

Please join hands with the Makerere University Endowment Fund as it works towards attracting & retaining the best faculty, providing scholarships, and investing in cutting-edge research and technology.