By Claire Zerida Balungi & Immaculate Bazira

History has its own language, and telling it in no particular style allows us to ruminate over our own journeys and stories. This is the tale of a once-mighty Makerere hall of residence which gave its former residents the days of their lives, but for others, sent chills down their spines. Adjacent to the Lions Leisure Park, Nsibirwa Hall stands in old wonder, as if in hard-learned mindfulness and constant surrender to the fight for might. A mix of men’s natural scents and of stuffy beddings accompany you through the dimly-lit green and white-ish corridor of Nsibirwa Hall, which was called Northcote Hall back in the day, renowned for its fame, terror and ‘hooliganistic’ culture which on many occasions shook the University, gathering whopping recognition, enough to make the country’s news headlines.

When it all started

Northcote’s story starts in 1948. According to a story published on the New Vision website in 2015, the hall’s construction commenced in the last days of 1948 as an action to commemorate the British government’s victory in the second World War which had concluded in 1945. The British donated generously towards the construction of decent accommodation for the students of Makerere at the time. In 1951, Northcote was erected, with two joint blocks; present-day Nsibirwa and Nkrumah Halls.

A picture of Northcote Hall taken in 1952

Northcote had over 400 rooms and was in fact once a stunning edifice whose enormous size and striking impression carried it like a wave, as it seemed to do with the men who walked out of the hall at daybreak. The distinctive architectural finesse captured the essence of time for admirers of both modern and medieval aesthetics. It’s said that Northcote’s appearance was somewhat similar to the Royal College of Music in West London.

In 1960, after the upper block (present-day Nkrumah) had pushed to secede from the lower block, the University Council split the hall into two. The lower block remained Northcote.

The hall’s culture ran as deep as the ink in the quills with which its paragons had written history. While the name Northcote sufficed, it did emulate the service of Sir Geoffrey Northcote, who served as Chairman of the University Council from July 1945 to 1948.

Whispers of a conspiracy theory which spoke of the Northcote residents as combatants or war generals surrounded the hall, although their fervor of hooliganism went beyond the spirit of principle that Sir Northcote’s character, their leader, endorsed as the New Vision article notes.

University life is often about what one chooses to do with their experiences.

During Kalungi Kabuye’s days (he left Northcote in 1988), Northcote was spirited but the culture wasn’t exactly abysmal, “Every hall had its own spirit/culture. There were confrontations between different halls, not just Northcote. When I was there, there was a lot of drumming by Northcoters, I was a sportsman, the culture was really good, students were proud, whether it was Kabinda (the name given to Nkrumah by Northcote when they split) or Lumumba, Northcote maybe more than the others, because we had the so-called army,” reminisces Kalungi.

The Northcote army and its generals

The residents, according to a 2015 New Vision article, had designated Northcote as a distinct state unto itself and found in themselves the capacities of generals. They erected a council that came to be known as Northcote State Supreme Revolutionary Council (NSSRCC) that convened its meetings in the hall’s attic. The Council was at one point chaired by Uganda’s former Inspector General of the Uganda Police Force, General Edward Kalekezi Kayihura a.k.a Kale Kayihura. Northcote was governed by a quartet of core pillars abbreviated as SSSD; Supremacy, Superiority, Speed and Determination.

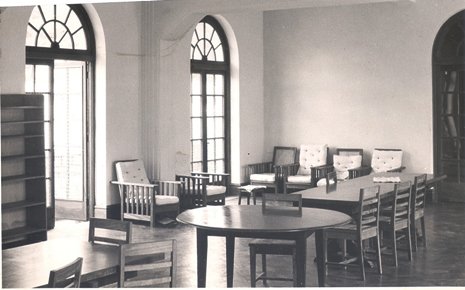

Northcote Hall Junior Common Room in 1952

Elvis Khisa who resided in Northcote from 1991 to 1994 swears that Northcote was fun before things went sour in the later years. “We used to dress in army fatigue, sing, support games with much spirit and drum – our social life basically was envied by other halls, they would get scared of us. Northcote was a command council. The culture minister was a field marshal, the speaker was a Brigadier et cetera,” narrates Khisa.

David Mills in his article, “Life on the Hill: Students and the Social History of Makerere” published in the Journal of the International African Institute wrote about the fear the “army-students” would instill in him in 1995 and likely many others.

“Renting a room on campus, I had awoken early one morning to the sounds of marching and shouting. My prefabricated 1940s-issue chalet shook on its stilts. Fearfully, I peered past the curtain, to see a phalanx of sweat-ridden young men in camouflage trousers. They chanted as they jogged past, heckled by a sergeant-major type figure. I assumed that it was an army detachment on a training run, and went back to bed.

At breakfast I mentioned the incident to my landlady, to find out that they were 'freshers', new students, at Northcote Hall of residence. They were being inducted into its quasi-militaristic culture, complete with uniforms, marching songs and passing-out parades.”

Northcote’s motto, “We either win or they lose” exuded a macho bravado of the generals and suggested a united front during the throes of war. The generals swore to a bro-code, a brotherhood during mobilization through student strikes where they invoked their coded term, “Weewe”, calling upon each other to act unitedly. They also swore by Omertà, a military version of the traditional code of silence compelling soldiers to uphold confidentiality in the face of adversity. The generals loyally exercised the codes even during the most difficult of times.

The end of Northcote

It was this solidarity that in fact turned Northcote’s soot into flames in 1996, much so that the hall had to cease being called Northcote, all residents dispersed into other halls, others expelled and the hall renamed Hall X as a new name was being deliberated upon. This horrendous account was also recorded by David Mills, “…during an end-of-term celebration in 1996. Several students from Northcote Hall attempted to put pepper and glass in food intended for students at two women’s halls. When the authorities found out, none of the students admitted responsibility, and the Hall declined to name the suspects. The University decided to punish all the students by closing down the Hall of Residence, breaking up Northcote's militarist culture and dispersing the students to other halls. The decision produced much dissent within the University, with the student body agitating for a less extreme punishment.

Disagreement within the University's ruling council resulted in a stand-off, exacerbated by the University's decision to impose a new registration fee on students as part of the move towards 'cost sharing', making Makerere more financially self-sufficient. This led to a student strike during which the Northcote students, led by their representatives in the guild council, attempted to break back into the hall and to occupy it. Running battles with riot police ensued, and thousands of pounds of damage was done. The police used tear gas to disperse the students, and many were arrested or injured. Thirty-five ringleaders were summarily expelled from the University. The rest of Northcote's students were either dispersed to other halls, or sent to find their own accommodation off-campus.” (D Mills - Africa: Journal of the International African Institute)

Dr Moses Musinguzi is one of the alumni that happened to join the hall that year in 1996. He joined as a fresher, from St Mary’s College Kisubi whose Makerere admission letter had Hall X, instead of Northcote. “We were all freshers. There were no second-, third- or fourth-year students in the hall. That whole clique of Northcoters that was known for hooliganism had been wiped out and Hall X was fresh ground. We didn’t have ancestors (people to treat us into the culture and tradition of the hall), we were all fresh. The only history we had was our high school and we were from different places, entering a hall without culture,” reminisces Dr Musinguzi.

The birth of Nsibirwa

In 1999, Northcote was renamed Nsibirwa Hall as an action of the decolonization movement of the 21st Century, after holding the interim name, Hall X for about a year. There is power in a name. Northcote carried with it a legacy of terror: “When we were in high school, especially us who studied in Kampala, we knew what was happening in Makerere University. Students who hoped to get admitted into Northcote were eager to carry on its legacies,” says Musinguzi, but that did not happen.

The main entrance to Nsibirwa Hall

The hall’s current name, Nsibirwa, is a nod to the influence of a great statesman, The Late Katikkiro Martin Luther Nsibirwa who had served and grown through the ranks as a political leader in Buganda. Despite his lack of formal missionary education, Nsibirwa had promoted education when he reigned as Katikkiro from 1929 to 1941 and in 1945 before he got assassinated on account of his acquisition of land from private hands for the Colonial Government to expand Makerere College. He had not officially been before a blackboard, but according to his daughter, Rhoda Nakibuuka Nsibirwa Kalema, he’d only learned to serve elders and to run errands as a page boy who lived at the home of Katikkiro Apollo Kaggwa of Buganda.

Nsibirwa was recognized by the current serving Katikkiro of Buganda, Charles Peter Mayiga, as a man of wisdom, determination, foresight and accomplishment at the May 2022 Makerere Annual Nsibirwa Public Lecture. His name has therefore been closely associated with the history of the establishment of the modern Makerere University.

As recorded in the 2015 New Vision article, Northcote’s spirit symbol is a huge-legged drum a.k.a Stereo which was bought by Dinwiddy, Northcote’s first warden. Stereo’s beat echoed with spirit during their gatherings such as the Freshers’ Initiation Ceremonies.

The lion’s sculpture at the main entrance of the hall symbolizes that each general has a lion’s heart. Besides it is a lioness to symbolize companionship.

In the grass just next to the parking lot in front of Nsibirwa is Lollipop, a funny-figured sculpture now standing in a new version. Lollipop is defined as “all-seeing, invisible and powerful” by Lawrence Nsimbe, a former disciplinary minister. The generals gather before Lollipop when they win in sport or battle to express gratitude to the visible-invisible, who-knows-if-gendered sculpture of both human and lion attributes.

Besides Lollipop is a sculpture of students marching in solidarity looking towards the hall’s entrance.

Today, the halls of residence reserve and practise their cultures but certainly not as staunchly as in the heyday. They still sing and dance at Sports events and porridge nights but some residents are almost not aware of the now-dilute culture. Keith Wabwire, who occupied the Nsibirwa Hall most recently says he’s barely been active in “their matters” as he was not sold to the culture and he only knew about it “from the outside”. Rivon Muhereza, the current warden of Nsibirwa Hall acknowledges that the hall has culture but what’s prominent is its student leadership and a Senior Common Room just like with the rest of the halls in the university. The cultures like singing during events like sports still happen but are not very spirited. “What stands out is the Nsibirwa anthem,” he says.

Prominent former residents of Northcote Hall

-Prof Ngugi Wa Thiong’o, African author,

-Gen Kale Kayihura, Former Inspector General of the Uganda Police Force

-Hon Abdu Katuntu, Politician and MP Bugweri

-Basil Bataringaya, Leader of Opposition in Milton Obote Government

-George Kihuguru, Former Dean of Students Makerere University

-Hon Emmanuel Lumala Dombo, Director Information, Publicity & Spokesperson NRM Party and Former Guild President

Related News

![]() Please join hands with the Makerere University Endowment Fund as it works towards attracting & retaining the best faculty, providing scholarships, and investing in cutting-edge research and technology.

Please join hands with the Makerere University Endowment Fund as it works towards attracting & retaining the best faculty, providing scholarships, and investing in cutting-edge research and technology.